How to Overcome Performance Anxiety: A Musician's Guide to Conquering Stage Fright

What Is Performance Anxiety?

Performance anxiety — commonly called stage fright — is your body's fight-or-flight response activating at exactly the wrong moment. Your heart races, palms sweat, hands tremble, and suddenly that passage you've played a thousand times feels impossible.

Here's the thing: this response isn't a flaw. It's your nervous system preparing for what it perceives as high stakes. The problem is that your brain can't distinguish between genuine danger and a room full of people waiting to hear you play.

You're in good company. The legendary cellist Pablo Casals experienced music performance anxiety even after giving more than a thousand concerts. Barbra Streisand stopped performing live for 27 years after forgetting the lyrics to a song. Chopin's letters reveal he was often terrified before performances. Even Luciano Pavarotti who radiated joy on stage, suffered greatly from nerves.

Nearly every musician experiences this at some point. The question isn't whether you'll feel it, but how you'll work with it.

The Mindset Shift That Changes Everything

Grammy-winning guitarist Bill Kanengiser teaches musician wellness at USC and has studied performance anxiety extensively. He points to his mentor Pepe Romero's radical reframe:

"Pepe flips it around and says it's not about me. I have nothing to do with this. The composer is over here and you're over there and I'm just this vessel and it just goes through me. Whether I do it perfectly or screw up completely makes no difference — I'll accept whatever happens."

This isn't about suppressing your nerves. It's about changing your relationship to them. When asked if he gets nervous, Pepe Romero gave this remarkable answer:

"When you're backstage and your knees are shaking and your hands are sweating and you can't breathe and your stomach is flipping and you think you're going to throw up — I love that. Because in that moment, my body is a battery that's being recharged with energy. Energy I need to go on stage, and when I go on stage, it flows out of me to the audience."

The insight is profound: don't push the feelings away. As Kanengiser puts it, "You don't fight it, you accept it. And you say this is good. This is good. I need this energy."

The Fastest Way to Calm Your Nervous System

When you need immediate relief, science points to one clear winner: the physiological sigh.

It's remarkably simple. Take a deep breath in, then take a second smaller breath on top of it to completely fill your lungs, then exhale slowly. That's it — a double inhale followed by a long exhale.

This works because it's a hardwired physical response. It activates your parasympathetic nervous system within seconds, and it works for anyone in any conditions. Do this 2-3 times before you walk on stage.

What a World-Class Violinist Learned About Breathing

Augustin Hadelich, one of today's most celebrated violinists, used to struggle terribly with nerves — especially around age 20-22 when he wasn't performing frequently. His bow would shake, particularly when starting softly, and he'd only feel comfortable 5-10 minutes into a performance.

What changed? Partly experience, but also a specific insight about breathing:

"I realized I can't slow my heart rate down — my heart is going to be very fast whenever I'm on stage. But the breathing I can control."

For violinists, Hadelich syncs his breathing to his bow arm: breathing out when moving toward the frog, breathing in toward the tip. This balances the natural weight of the bow and creates consistency between practice and performance. But the deeper point applies to all musicians: when everything else feels out of control, breathing is something you can control.

"The worst thing you can do on stage is to stop breathing," he notes. When extremely nervous, we sometimes freeze like a deer in headlights. Conscious breathing prevents that.

Redirect Your Energy, Don't Fight It

Behavioral researcher Vanessa Van Edwards studied with sports psychologist Don Greene, who has coached the U.S. Olympic swim team and trained Navy SEALs. His approach to performance anxiety isn't about eliminating nerves — it's about redirecting them.

One of his key techniques: pick a focal point. Choose a far-off, unimportant point in the back of the room. When you feel anxious, mentally hurl your nervous energy toward that point. As Van Edwards explains, "Dr. Greene isn't asking you to ignore your nervous energy — he's asking you to redirect it."

This works because telling yourself "don't be anxious" doesn't work. But giving that energy somewhere to go creates relief. Van Edwards describes it as "the amazing lightness of throwing off a heavy backpack."

Another key insight: the precursor to performance anxiety is often confusion or chaos. "When our thoughts are scattered, when we're rushing around, we don't feel centered." Her solution: form one clear intention before you perform. Keep it positive — not "don't mess up" but "stay confident" or "play my heart out."

Mental Training: What Musicians Can Learn from Athletes

Pianist and researcher Miho Ohki noticed something important: athletes prepare mentally for competition far more systematically than musicians do. There are sports psychologists helping athletes integrate mental training into their daily routines. Why not musicians?

She developed a framework with four categories of mental training techniques:

Activation regulation — Achieving optimal arousal through relaxation techniques like breathing and autogenic training (a form of self-hypnosis).

Motivation regulation — Goal setting, visualization, and attribution training. Attribution training is particularly interesting: it's about understanding why we failed or succeeded, and attributing failure to things we can change (like effort or strategy) rather than fixed ability.

Emotion regulation — Increasing awareness, controlling attention, and changing negative thoughts to positive ones. Good performers can switch their attention between internal focus (like individual fingers) and external focus (like the melody or the room) quickly and comfortably.

Mental practicing — Practicing without making any sound on the instrument, which helps you internalize what actually happens in the music.

In her research, participants who did mental training for six weeks before a concert showed significantly decreased anxiety and clearly increased self-confidence compared to performing without it.

Her personal transformation: "I used to often have stage fright during concerts, especially at crucial moments. Now, I know how to use my stage fright as an advantage and positive energy and not see it as a drawback."

The Question That Puts It All in Perspective

Near the end of her TEDx talk, Ohki asks the question that cuts through everything:

"Why do we actually play music? Why do we perform in front of an audience? Sometimes we tend to think that people judge us as a person when we play an instrument, but we actually want to share music, right? Because it's just beautiful and powerful."

This reframe — from "I'm being evaluated" to "I'm sharing something beautiful" — echoes what every expert in this article discovered in their own way. Pepe Romero sees himself as a vessel. Augustin Hadelich focuses on what he can control. Don Greene redirects the energy rather than fighting it.

The nerves don't disappear. But they transform from an obstacle into fuel.

Practical Techniques to Use Before Your Next Performance

Based on everything above, here's a concrete pre-performance routine:

Days before: Visualize the complete performance going well (5 minutes daily). Practice under performance-like conditions — don't get too comfortable. Set a clear, positive intention for what you want to achieve.

Hours before: Avoid excess caffeine and sugar (they worsen shakiness). Eat carbs for energy. Do a body scan, progressively relaxing from head to toes.

Minutes before: Do 2-3 physiological sighs (double inhale, long exhale). Pick a focal point in the room for redirecting nervous energy. Remind yourself of your process cue — how you want to feel while playing.

Walking on stage: Maintain confident posture even if you don't feel confident. Remember: your body is a battery being recharged with energy you need. The audience wants you to succeed. They came to enjoy music, not to catch mistakes.

Practice Performing With a Supportive Audience

There's one challenge none of these techniques fully solve: the gap between practicing alone and performing in high-stakes situations.

Augustin Hadelich noted that he was most nervous when he wasn't performing frequently. Bill Kanengiser acknowledges "we can all get better at it" through experience. But how do you get that experience without the high stakes?

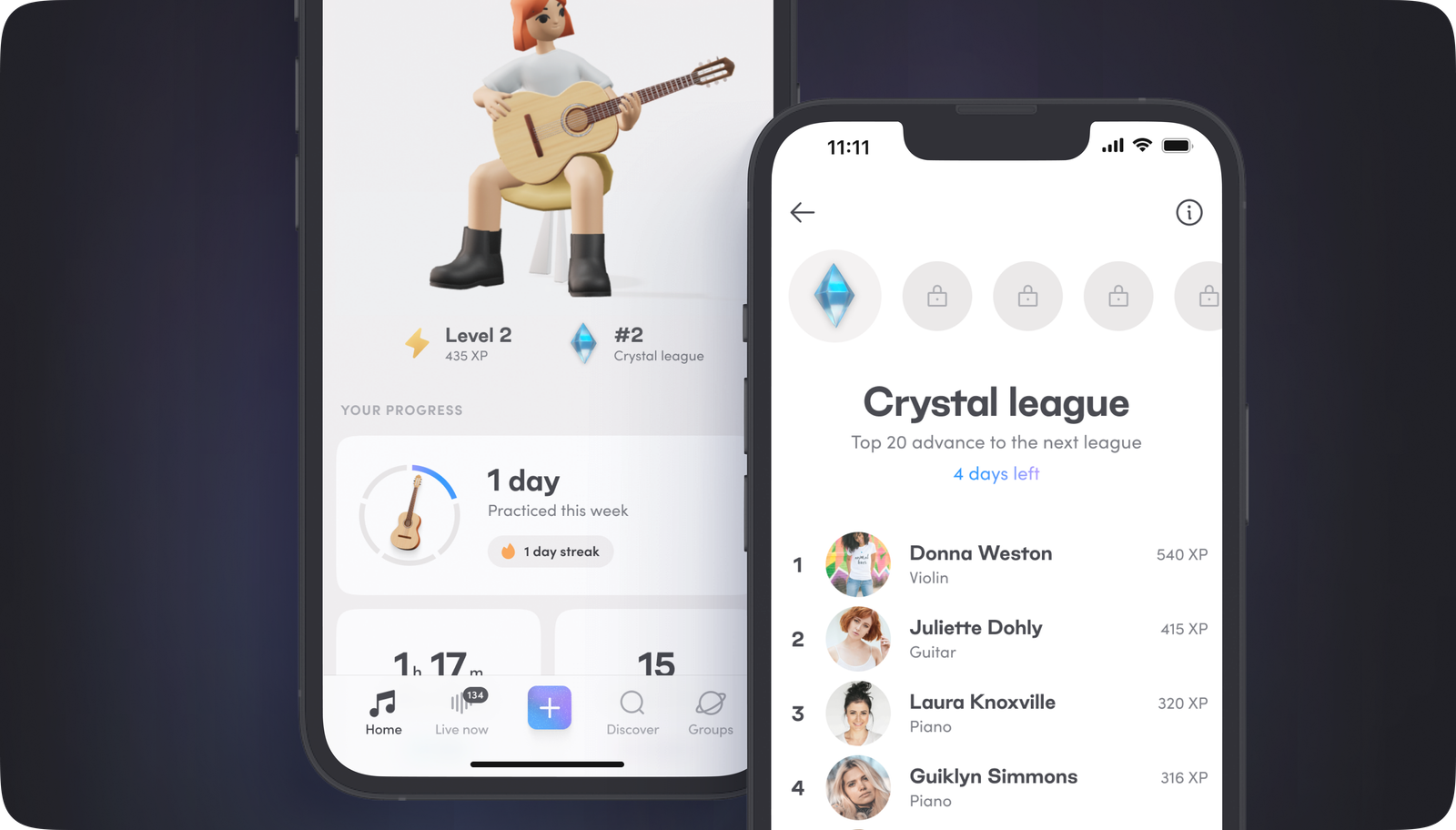

Tonic was built to fill this gap. The app lets you practice in live, audio-only Studios with other musicians listening in real-time. It's not a performance — you're just practicing, but with an audience. This simple shift helps normalize the feeling of being heard.

As you build confidence, you can try Performance mode — a dedicated space for sharing polished pieces. The progression from private practice → public Studios → Performance mode mirrors how confidence actually develops: through gradual, supported exposure.

Musicians preparing for exams have found this especially valuable. Tonic has partnered with the Royal Conservatory of Music (RCM) and is working with ABRSM to help students get comfortable being heard before exam day.

"Amazing app! Great to help with performance anxiety! I always practice performing now on a daily basis."

"It is amazing how much people will practice when they have a supportive audience. Simply brilliant!"

The app is completely free. Download Tonic and start building your performance confidence today.

The Bigger Picture

Performance anxiety isn't something you eliminate — it's something you learn to work with. The goal isn't to feel nothing; it's to channel that energy into your music.

As Kanengiser reminds us, "Why do we get so nervous? Because we care. We've spent all this time and we desperately want it to be the way we want it."

That care is a good thing. It means music matters to you. The techniques in this article — the breathing, the reframes, the visualization, the gradual exposure — don't take away the caring. They help you express it fully, without your nervous system getting in the way.

Every great performer you admire has dealt with nerves. The difference is they've developed strategies, built experience, and learned to trust themselves.

You can too. Start small. Breathe. Remember why you play. And keep putting yourself out there — one supportive audience at a time.